My 7th grader’s science teacher is letting her opt out of dissecting a rat, as a conscientious objector. She says the rats were murdered just so her fellow students could slice them open for a peek inside, and that is NOT okay with her. My husband, a doctor who places great value in the tactile experience of dissection to plumb the mysteries of anatomy and physiology, says opting out is NOT okay with HIM.

I, too, dissected stuff in my day, without much compunction–even though I’m a card-carrying bleeding heart who won’t even kill a stink bug. (I euthanize them in the freezer). As I encourage my daughter to participate, in spite of her objections, so she can learn from the experience, I start asking myself: What did I learn by eviscerating a frog, fish, and fetal pig? I did find value in it, a sense of discovery. But perhaps there is a dark underbelly of dissection that I haven’t thoroughly probed.

I trust animals that become dissection specimens have been euthanized according to humane standards. And frankly, euthanasia is a much gentler death than many humans experience, or than wild animals suffer in the jaws of a predator or after prolonged starvation or disease. But what of the lives of these animals before euthanasia and dissection? Were they treated humanely by people who cared about their welfare and understood their needs? Is this even knowable? Would I want to know? That is, perhaps, a topic for another day.

My daughter can be melodramatic, but her feelings are genuine. Her concern is valid, though unexamined. Her teacher is empathetic and won’t force the issue. I remain conflicted. I value a science education and respect the teacher’s choice to provide a hands-on zoological deep dive. But my heart bleeds when animals suffer, and surely the life of a lab rat before it becomes a dissection specimen cannot be devoid of suffering? Still, the rat my daughter will (or, according to her, will NOT) dissect has already lived and died; if she doesn’t make good use of it now, doesn’t that add insult to injury? Has the rat died in vain, only to be wasted?

I encourage my daughter to research the lives of lab rats, so her feelings can be guided by facts, heart and mind in sync. I share a coping strategy of my own: when I witness an animal suffering, I try to symbolically offset it with an act of kindness toward another animal–a pet, a shelter animal, a wild critter, whatever. Maybe she can counterbalance her rat dissection by donating to a rescue organization, putting up a bird feeder, playing an extra-long ball game with our dog, or some other gesture that feels right to her.

Whether my daughter comes down on the side of dissecting or objecting, I’ve decided to use this space to cleanse my conscience about the whole thing by honoring the rat. How are rats special and worthy of awe? Let me count the ways:

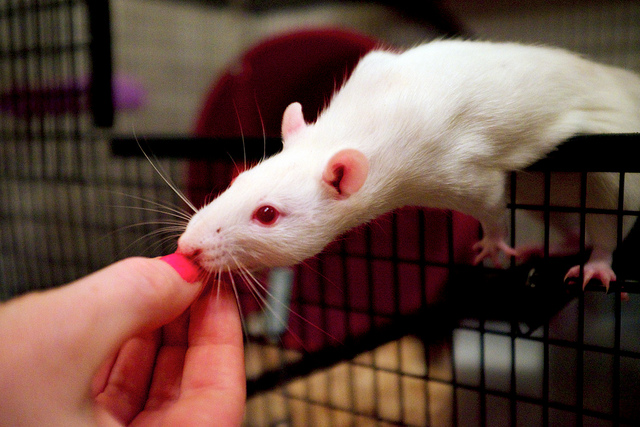

1. Rats laugh when you tickle them.

So you’ve never heard a rat dissolve into a fit of giggles? That’s because the sound they make is supersonic–exceeding the highest frequency human ears can perceive. In 1996, when neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp and his team used a bat monitor to listen in on rats playing, they picked up a 50 kHz twittering noise. Panksepp had been searching for a vocalization associated with play to use as a quantitative metric in his research, and there it was. As he reflected on the emotional significance of the sounds, it dawned on him that, given the context, maybe the rats were laughing.

Crazy? Plenty of his colleagues thought so. But further studies replicated Panksepp’s findings and substantiated his hunch. Consistently, rats expressed these chirping sounds only in fun situations, like play with other rats and tickling by humans. How do we know they think tickling is fun? Rats who love tickling chase after hands to solicit more tickles. Some rats valued tickling even more than treats as a training reward. Scientists have even purposefully bred a strain of tickle-loving rats for further research.

Naturally there was plenty of skepticism about Panksepp’s theory. I say naturally, because humans habitually seek–and defend–distinctions between ourselves and animals, loath to credit beasts with those qualities and capacities upon which we base our superiority. For much more on this, read Frans de Waal’s spellbinding book Are We Smart Enough To Know How Smart Animals Are?

Naturally there was plenty of skepticism about Panksepp’s theory. I say naturally, because humans habitually seek–and defend–distinctions between ourselves and animals, loath to credit beasts with those qualities and capacities upon which we base our superiority. For much more on this, read Frans de Waal’s spellbinding book Are We Smart Enough To Know How Smart Animals Are?

So we object to sharing a trait like laughter with a lowly rodent. But think about it. If rats make a distinctive utterance in the same circumstances that make humans laugh–and we know this sound represents pleasure because rats keep wanting more of it–then you can call it whatever you want, but it’s hard to prove it’s not laughter.

Studying rat chuckles might sound frivolous, but investigating rat behavior during positive and negative emotional states can be applied to the wider scope of mental health and mood disorders in humans. And if a rat has to endure scientific experiments that may include aversive experiences, it’s heartening to think laughter could also be part of this life.

2. Rats empathize, cooperate, and share.

Rats will break their friends out of jail. In a study published in Science magazine in 2011, Inbal Bartal and his colleagues encased a rat in a clear plastic box, stashed a piece of chocolate (a favorite rat treat) in another, and then turned one of the trapped rat’s pals loose to see what he would do. The free rat quickly solved how to unlatch the boxes–no surprise given rats’ dexterity and shrewdness. But instead of leaving the other rat locked away while hogging all the chocolate, he first emancipated his friend and then shared the treat with him. And loads of other rats went on to do the same. This clever video from How Stuff Works includes a snippet of this experiment.

In another study, rats in separate enclosures took turns giving each other food. In the first phase, Rat #1 could serve Rat #2 either bits of banana (rat candy) or scraps of carrot (a decidedly meh food). In phase two, Rat #2 could dole out cereal to his partner at whatever rate and on whatever schedule he chose. Rats who had dined on banana were quick to supply their server with plenty of cereal. Those who just got crummy old carrots gave less cereal to their stingy partner, and took their sweet time doing it. Rats recognized who had been good to them, calculated how good, remembered it, and reciprocated proportionally–kind of like people do.

3. Rats can learn and perform eye-poppingly awesome tricks.

We hear a lot about lab rats learning to run mazes or press levers, so we know they can master some simple chores. But if you want a sense of how much is going on in their little pea brains, check out this video by sixteen year old rat lover Abby Roesner. She’s trained her pets to do some stunning stunts, including dunking a miniature basketball, fetching her a Kleenex when she sneezes, and pulling money out of her wallet!

4. Rats can detect landmines and sniff out tuberculosis.

In one of the most gripping (to me, anyway) TED Talks of all time, Bart Weetjens showcases his “Hero Rats”, which he trains to locate buried landmines in Mozambique, Angola and Indochina. Why use rats? Because they have a superpower: an ultrasensitive nose. Rats have more DNA devoted to the sense of smell than all other mammals except African elephants. Weetjens’ rats learn to recognize the scent signature of mines, scratch at the ground when they find it, and return to their trainer for a nibble of banana. They’re also trained to wear a harness and walk on a leash.

Once they’ve attained proficiency, the rats undergo a certification test. Those that pass become accredited detection animals, just like bomb sniffing dogs but–as Weetjens points out–they’re 80% cheaper to train and maintain. Plus, because rats are so lightweight, they don’t trigger land mines to detonate. Once a rat identifies a mine, a de-mining team is called in to disarm it. More than 50,000 explosives have already been deactivated with assistance from Hero Rats.

Weetjens’ rats are also helping diagnose tuberculosis (TB) in human patients. The standard diagnostic method recognized by the WHO (World Health Organization) is to examine sputum (gunk coughed up from the lungs) under a microscope for the presence of TB. Visual inspection at best picks up only 60% of actual cases, though, so many sick people miss out on early treatment. But the nose knows; rats seeking the faint tar-like odor TB patients exude rarely come up with a false negative.

Plus they’re faster by far. It takes a rat just two hundredths of a second to sniff out TB. What would take a full day with microscopy, a rat can process in seven minutes; given a day, a rat can test 6,000 samples. In Tanzania Weetjens’ HeroRATS have already screened nearly 300,000 sputum samples and correctly diagnosed more than 7,000 patients whose TB was missed by microscopy.

So. Rats. Wow. Do you have a rat story? A deep admiration for rats in general, or one rat in particular? Have you ever dissected a rat, or refused to, on moral grounds–or any other grounds for that matter? Let me know!

For more details:

http://www.radiolab.org/story/91589-is-laughter-just-a-human-thing/

http://discovermagazine.com/2006/dec/20-things-rats

http://www.wired.com/2013/09/tickling-rats-for-science/

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/334/6061/1427

http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/11/2/20140959

I would suggest that your daughter has every right to decline participation. Your husband’s reaction (being an obviously well educated man) is disappointing. Voluntarily entering a career path that involves cutting into living or dead creatures is one thing. Forcing an impressionable child to involuntarily participate in such events is a totally different situation. She may well learn valuable information from this project, but she may also be impacted negatively which could affect her for many years.

There is a time for teaching discipline; a time for respecting authority, and a time for simply “getting the job done”…. and all that may well be fine with accepting (e.g.) Latin as a mandatory school subject, or sports as a necessary participation. It would be very insensitive to force a child to cut into a creature when she clearly has issues with the idea.

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughts, Ray! Hard to know the best way to handle such things. For me, at least it became a fun opportunity to learn more about rats!

LikeLike